This document describes a system for categorizing domain name policies by identifying central aspects that forms the way the policy is experienced, and sorting the policies according to those aspects. It is important to be aware of the fact that many other factors (prices, the possible organization of the top-level domain into second level domains etc.) may also play a part in how a specific domain name policy is experienced. Still, policies that are in the same category shares some of the same advantages and disadvantages and as such the categorization may be useful.

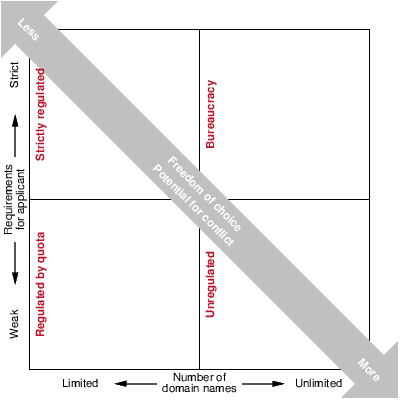

When comparing different domain name policies there appears to be two central aspects which to a large degree forms the policy. One aspect is the number of domain names any applicant may hold; the other is the requirements placed on the applicant at the time of registration of a domain name. (Common requirements in this context are that the applicant is able to provide documentation showing that he has rights to the word he intends to register or a prerequisite that the applicant is an organization.) Based on these two central factors, domain name policies can be divided into four main categories (see figure 1).

Strict requirements for the applicant

Common to both of the upper categories is the priority placed on preventing domain name registrations by applicants who have no rights to the name in question. To accomplish this, the applicant is subject to strict requirements, among them the requirement that the applicant is able to provide documentation showing that he has rights to the word he intends to register. Other requirements may be applied as well, e.g. a requirement for the applicant to have a local presence in the geographic area the top level domain corresponds to. Applicants are screened through the different requirements, and the "first come, first served" rule does not apply until all requirements are met. This results in a lower potential for conflicts regarding domain names, but at the same time restricts the applicants' ability to freely choose their domain names.

Strictly regulated

In the upper left corner of the figure are the domain name policies based on the premise that the applicant may hold a small number of domain names and that each domain name is evaluated against strict application requirements. Many top level domains started in this category, with a strictly regulated domain name policy, and then moved on to less regulated policies after a while.

The restrictions on the number of domain names per applicant limits the possibility for extensive domain name speculation and warehousing. And since there is a limit on the number of domains an applicant can have, some flexibility is possible when it comes to the requirements placed on the applicant (e.g. allowing the applicant to refer to the name of the organization, a trademark, a tradename, a logo or other forms of documentation when documenting his rights to the domain name.) The limit on the number of domain names also means that even though domain name policies in this category require manual evaluation for each application it scales fairly well, and there is no need for an extensive application processing apparatus.

Bureaucracy

The upper right corner holds domain name policies that maintain strict application requirements, but allow an unlimited number of domains registered per applicant. Under this category one of the essential tasks of the registry is evaluating documentation from applicants. When there is no cap on the number of domain names, the application requirements must be stricter compared to what is the case when there is a limited number of registrations. External evaluation of the documentation performed by lawyers or patent offices may therefore be an option. Processing a large amount of applications requiring manual evaluation necessitates a large registry. The fact that several entities may be consulted could also result in longer processing times and higher costs per domain name. The advantage of this policy is that unlike the strictly regulated policy it does not limit an applicant that have many trademarks from registering all of them as a domain name, no matter how many they are.

Weak requirements for the applicant

Common to both the lower categories is that freedom of choice for the applicant is given a higher priority than the prevention of illicit registration of domain names. This means that the registry does not take into consideration whether the applicant has any rights to the domain name. There is no prescreening of applicants; whoever applies first gets the name in question registered. The potential for post-registration conflict level is higher under these domains than under the more restrictive domains.

For those top level domains where there is almost no requirements for the applicant an additional drawback may be that there is a lower predictability in terms of who operates the various domain names, as opposed to what is the case under a domain name policy that requires the applicant to have a local presence in the country connected with the TLD or requires the applicant to be a registered organization. On the other hand, fewer requirements put on the applicant also means a greater flexibility for any applicant to choose the domain name they want.

Regulated by quota

In the lower left corner are the domain name policies with weak application requirements, but with a limited number of domains allowed per applicant. Here, the applicant's freedom of choice takes precedence over the desire to prevent illicit registration of domain names. However, the limited quota per applicant is an attempt to place a certain restriction on speculation and warehousing. These policies requires little bureacracy, and may be implemented by a small registry.

Unregulated

The lower right corner holds domain name policies with few or no application requirements, and no restriction on the number of domain name registrations. Just like in the previous category, the applicant's freedom of choice is given precedence. The unlimited number of domain names allowed per applicant means that warehousing (the collection of many domain names on one applicant for later sale) may be a problem unless other mechanisms, like pricing, is used to limit the number of domain names an applicant finds practical to hold. The policies in this category scales well and requires little bureacracy.

Handling of Conflicts

Conflicts regarding the right to a domain name may arise under all domain name policy models shown above. Irrespective of the extent of the evaluation performed by the registry, the final responsibility for the choice of domain name resides with the applicant. Hence the regular conflict procedure of most registries is to inform the parties how to get in touch with one another, but otherwise refrain from any involvement in the conflict.

If the parties cannot be reconciled, the conflict may be solved by means of the legal system in accordance with the applicable legislation on name rights. In this regard, domain name conflicts are no different from other conflicts regarding name rights. The drawback is that this may be a time-consuming process, and in some cases, it has been difficult to determine which laws apply. This applies in particular to the generic top level domains, but the problem has also occurred in the national domains. To alleviate these problems, some top-level domains have some form of alternative dispute resolution that may be used instead of going to court. It is also important to be aware of the fact that even under the unregulated domain name policies conflicts are few in comparision to the number of names that are registered.

Moving from one category to another

Unfortunately there is no "perfect" domain name policy that will satisfy all needs. All the domain name policy models have their advantages and disadvantages, and which model is chosen for a specific top-level domain depends on what the local Internet community judges to be the most important criteria. If flexibility and freedom of choice is prioritized over the desire to stop illicit registrations domain name policies with weak requirements will be chosen. If a desire to restrict warehousing, and to some degree domain name speculation, is predominant a policy with a limit on the domain names allowed per applicant will be chosen.

And as the needs of the local Internet community changes, the domain name policy will be changed as well. A typical example is a top-level domain that starts with a rather restrictive domain name policy, and then later liberalises the policy by either removing the limit on the number of names an applicant may hold (moving from the "strictly regulated" category to "bureacracy") or by decreasing the requirements put on the applicant (moving from "strictly regulated" to "regulated by quota") or doing both at once (moving from "strictly regulated" to "unregulated").

The important thing to be aware of when changing from one model to another is that while liberalising a restrictive policy is fairly easy, going back again and restricting a liberal policy is very hard, so one should make sure that the local internet community understands the consequences of the liberalization before it is made.

Domain name policies among ccTLDs

Having learned that there is no such thing as a "perfect" domain name policy and that each top-level domain will modify their policy over time, it may still be interesting to examine whether there are global patterns as to which domain name policy model is most popular at present.

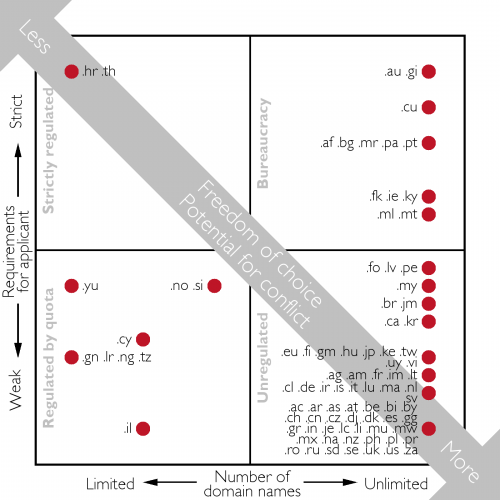

The figure below shows the domain name policies used by some of the ccTLDs in the world as mapped into the four different policy categories. To place the domain name policies correctly on the scale of requirements for applicants a value has been computed for each policy depending on how many of the three following items the policy requires from the applicant:

- a requirement for the applicant to provide documentation showing that he has rights to the word he intends to register. This requirement is weighted more heavily than the other two. Any policy having this requirement ends up in one of the upper categories, any policy not having this requirement ends up in one of the lower categories.

- a requirement for the applicant to be an organisation.

- a requirement for the applicant to have a local presence in the geographic area the top level domain corresponds to (requiring an administrative contact in the country counts as having half fulfilled this requirement).

While many top-level domains started with a strictly regulated policy, few of the domain name policies in this figure are currently in this category. This reflects the general move towards more liberalized domain name policies that has taken place over time.

It is also clear that most top-level domains within the survey seem to currently prefer a domain name policy that does not set any limits on the number of names an applicant may hold. There are some exeptions, most of them have a policy regulated by quota.

While the majority of the top-level domains in this figure allows an unlimited number of domains per applicant, the degree of requirements for the applicant varies. A few requires the applicant to document rights to the domain name (Australia, Bulgaria, and Mauretania are some examples of ccTLDs who do this). The large majority resides in the unregulated area and does not require any documentation of rights. Some still require either a local presence, or that the applicant is an organization (or both), hence the spreading within the category.

With the steady growth in use of the Internet has come a steady push for changes in domain name policies. Unlike earlier, todays large companies are rarely satisfied with having only one Internet presence. They want to have multiple domains each of which focuses on different services or customer groups, and they want an easy registration process with few hurdles. Interestingly too, many of them are increasingly intent on using a domain name not so much as an identifier for a service or a company, but rather as simply a device to generate and direct traffic towards a specific website or service.

In sum, these factors have resulted in a general move towards more liberalized and flexible domain name policies. The fact that liberalizing a policy is almost always a one-way change has served to reinforce this process.

The domain name policy for .no - an example of moving from one category to another

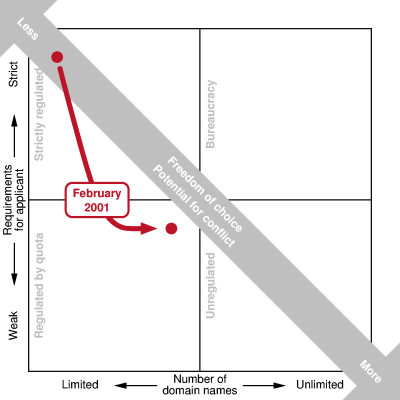

The name policy for .no used to fall into the category of strictly regulated name policies. The policy required that the applicant was an organization and able to document its affiliation with the name, but was somewhat more flexible than Sweden and Finland (who at that time also had a strictly regulated policy) with regard to what was considered acceptable documentation.

In February 2001, Norid (the registry for .no), in collaboration with Post- og teletilsynet (the Norwegian Post and Telecommunication Authority), carried out a transition to a more liberal domain name policy for the .no domain. The changes in the domain name policy were triggered by earlier feedback from the local Internet community signaling that the previous policy was too restrictive. Hence, the basis for the name policy changes was the desire to grant the applicants a greater freedom of choice.

In order to achieve this it was proposed to allow an increased number of domain names per applicant. Maintaining the strict application requirements while allowing a greater number of domain registrations would necessitate a larger and more bureaucratic apparatus for the evaluation of applications. Such a solution would certainly prioritize a high quality within the name space, but would also result in increased processing time and cost per domain name. Hence, Norid considered this solution inadequate. Moreover, feedback from the local Internet community signaled that the application requirements under the old policy were too strict. Norid therefore proposed an easing of the application requirements. In this way, more applications could be processed without expanding the processing apparatus.

As to the easing of application requirements, Norid proposed the removal of the requirement concerning documentation of the affiliation between the name and the applicant. When it came to the requirement that the applicant is an organization, experience from Denmark had shown that maintaining updated contact information without requiring any form of unique applicant identification is difficult. The result could be many domain names that did not function properly (e.g. mail delivered to the wrong address, inaccessible web servers), which Norid considered to be detrimental. Until then, the name space under .no had maintained a high technical quality, with an emphasis on registered domain names also being operative. Norid found it important

to maintain this quality, and hence proposed keeping the requirement that the applicant must be an organization.

Granting access to more domain names and softening the application requirements would result in a higher potential for conflicts. This is particularly evident in domains such as .com. Norid found it desirable to try to keep the potential for conflict at a lower level than what was the case for .com. In order to achieve this a policy regulated by quotas with a cap on the number of domain names was proposed, in addition to the proposal to keep the requirement that the applicant should be a clearly identifiable organization.

Based on the experience from other domains, Norid considered it likely that the proposed change would lead to more conflicts. This would again place a greater strain on the legal system, but it was assumed that the cap on the number of domain names would keep the number of conflicts at a manageable level. In addition it was decided that if a later evaluation showed that the strain on the legal system reached a problematic level the local Internet community would be consulted on the issue of an alternative dispute resolution process.

To ensure that the proposal was in accordance with the desires of the Norwegian Internet community, Norid invited the public to submit comments during the fall of 1999. The conclusion from the feedback gathered during the consultation period was that the majority of the participants desired a change in the domain name policy for .no in accordance with Norid's proposal. Hence, the proposal was implemented. (Information about the change of policy and an evaluation of the process are available in Norid's policy archive, go to Revisjon 11. The documents are in Norwegian only. )